Defining Mental Health

What is mental health?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes mental health as the emotional, psychological, and social well-being of an individual. Our mental health affects how we think, feel, and act and is indicative of how we respond to stress, how we engage in the relationships (personal, familial, and professional), and how we make healthy choices.

It is just as important as physical health and is worthy of care from childhood through adulthood.

(CDC, 2021)

Poor Mental Health vs. Mental Illness

The two terms are often used interchangeably but are not the same.

For example, a person with poor mental health may never have be or never be diagnosed with a mental illness.

However, a person diagnosed with a mental illness may experiences periods of poor mental health.

For example, someone may be struggling with their job, which may lead to feelings of low mental health. This does not mean they will suffer from a mental illness.

Similarly, someone may have a diagnosed mental illness like OCD but may be able to manage this effectively and lead a healthy life. Thus, the individual may have a mental illness but good mental health.

(CDC, 2021)

Poor Mental Health vs. Mental Illness

Mental health may change over time and is dependent on the resources and coping mechanisms of the person experiencing poor mental health. Poor mental health may arise from many stressors related to the social, political, and systemic determinants of health. Racism, sexism, homophobia, gender inequality, political strife, etc. may have an impact on a person’s ability to cope.

(CDC, 2021)

Mental Illness

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) describes a mental illness as conditions that may affect a person’s thinking, feeling, behavior, or mood and may impact that person’s daily life or their ability to relate to others.

Common Mental Illnesses:

Prevalence of Mental Health

The CDC reports that mental illnesses are common in the United States.

- 1 in every 5 Americans will experience a mental illness in a given year

- 1 in 5 children have ever had or now have a debilitating mental illness

- 1 in 25 Americans lives with a serious mental illness

- More than 50% of Americans will be diagnosed with a mental illness during their lifetime

(CDC, 2021) (NAMI)

Causes of Poor Mental Health and/or Mental Illness

Trauma

Abuse

Racism and discrimination

Witnessing Violence

Experiences related to chronic illnesses

Chemical imbalances in the brain

Use of illicit drugs or alcohol

Work stressors

Feelings of Loneliness or Isolation

Parenting

Relationship stressors

e.g. intimate, professional, familial, friendships)

(CDC, 2021)

Allostatic Load & Mental Health Inequities

Allostatic Load

Allostatic load is the increased risk of disease and dysfunction that are the results of repeated and chronic stress and/or stressful events on an individual or community (ScienceDirect, Allostatic load).

Historically excluded and marginalized communities have, in particular, experienced a unique and oppressive set of stressors over the course of history – especially in America.

Generational Trauma in the Black Communities of America

Though experiences of being Black in America vary greatly, as Black people have a dynamic range of lifestyles and experiences, there are some shared cultural and external factors that have defined the resiliency and mental health of the Black community.

Mental Health in Black Communities

There are some shared cultural experiences that have had a positive impact on the resiliency of the Black community in America. Those assets include religious networks, the importance of community, social support networks, family connections, expressions through arts, math, and the sciences.

Conversely, chattel slavery, Jim Crow laws, racism, discrimination, microaggressions, purposeful exclusion from wealth-building policies like the GI bill, FHA loans, etc., redlining, segregation, policy brutality, racism in healthcare, and the like have all been traumatizing and stressful factors within which Black communities must navigate. This has created, according to the Office of Minority Health at the Department of Health and Human Services, a higher propensity in Black Americans for symptoms related to emotional distress.

One study concluded that independent of socioeconomic status and health behaviors, allostatic load could partially be explained for the higher mortality rates among Black Americans across all therapeutic areas. (Duru et al., 2012)

Barriers to Mental Health in Black Communities

Several barriers contribute to a lack of access to mental health in Black communities

- Socioeconomic factors: lack of access to health insurance and lack of access to socioeconomic resources contribute to poor mental health

- Mental Health Stigma: A negative stigma on mental illnesses, conditions, and poor mental health is rampant within the Black community. Research has shown that about 63% of Black people view struggling with mental health or mental illnesses is a sign of weakness. This perception can lead to shame and inhibit people from seeking help.

- Faith & Spirituality: Faith and faith-based practices can be important assets and coping mechanisms for people struggling with mental illnesses. However, many communities of color, especially the Black community, often view faith-based leaders and organizations as their only option for mental health treatment. The strength of faith and faith-based institutions can be coupled with professional mental health treatment to improve mental illnesses.

- Racism in Mental Healthcare: Black people experiencing poor mental health or mental health issues often times face provider biases and systemic barriers when attempting to seek care. This turns the individuals away from seeking services altogether.

Mental Health in Asian American and Pacific Islander Communities

The Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community consists of approximately 50 ethnic groups speaking over 100 languages. NAMI estimates that over 24 million Americans, or 7.3% of the U.S. population are of AAPI descent.

While ethnic and community identity are invaluable to the experience of the AAPI community, only two-thirds identify with their ethnicity or country of origin.

This sense of communal identity and strong cultural connections can contribute to higher resiliency in the face of racial discrimination. Having such ties can reduce the risk of death by suicide.

Unfortunately, second-generation AAPI communities often struggle to balance their cultural and familial ties with the unnecessary and inequitable pressure of assimilating to American society. This can be a driver of poor mental health among AAPI communities.

Barriers to Mental Health in AAPI Communities

NAMI notes that in 2019, the AAPI community had the lowest help-seeking rates of any other historically excluded or marginalized community. Several barriers to mental health may be the related.

- Language barriers

- Stigma and shame

- The myth of the model minority

- Faith and spirituality

- Immigration status

- Health insurance barriers

These barriers may further the inequities that exist among the AAPI community.

Mental Health in Hispanic and Latinx Communities

Like many diverse communities the Hispanic/Latinx communities of the U.S. have a strong sense of identity and culture and are tied to their “familismo” – a strong sense of connection, attachment, and duty to one’s family.

People of Spainish, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Haitian, Central American, and South American descent make up the Hispanic/Latinx populations of the U.S.

While none of these communities are a monolith, most share common cultural identities and speak the Spanish language.

It’s important to remember that cultural identity is extremely valuable in Hispanic and Latinx populations. Some may not even use these terms to describe their identity, rather they may describe their identities in the context of their country of origin.

It’s also important to understand the intersectionality of race and ethnicity across Hispanic and Latinx populations. Some may identify as Black as well, thus describing their identity as Afro-Hispanic or Afro-Latina/o.

Barriers to Mental Health in Hispanic and Latinx Communities

Hispanic and Latinx communities face disparities in access to mental health services and quality of treatment. NAMI estimates that more than half of Hispanic and/or Latinx adults 18-25 years of age with mental illnesses may not receive treatment. That is, about 34% of Hispanic and/or Latinx Americans receive mental health treatment versus 45% of the general U.S. population. Barriers may include:

- Language Barriers

- Socioeconomic Status

- Lack of Cultural Humility and Culturally Responsive Care

- Immigration Status

- Acculturation

- Stigma

These barriers further the pervasive mental health inequities that exist.

Mental Health in Indigenous Communities

Indigenous peoples refers to all populations who were living in the U.S. prior to European colonization. Indigenous peoples currently comprise approximately 1.5% of the U.S. population.

Indigenous peoples thrived and prospered before colonization. This fact must be acknowledged when engaging in mental health conversations.

Over 574 federally recognized indigenous nations exist today.

Indigenous peoples also have a shared cultural connection to and respect for the land, nature, sharing connectedness to the past, strong family bonds, holding reverence to the wisdom of elders, and maintaining traditions.

These respects for land and nature are some of the reasons why Indigenous peoples were devasted by colonization. Forced removal of populations, forced removal of children from their families, forced assimilation, mass genocide, blockages of waterways, deforestation, and displacement were all acts imposed by colonizers that further devasted Indigenous nations.

These centuries-long oppressive tactics have undoubtedly contributed to the allostatic load of generations of Indigenous nations.

NAMI reports that nearly 19% of Indigenous adults experienced mental illness last year and that alcohol and substance use at younger ages increased. Moreover, death by suicide rates among Indigenous nations are double that of white youth.

Barriers to Mental Health in Indigenous Communities

Pervasive inequities keep Indigenous communities from accessing mental health care. Barriers exist in the following areas:

- Rural and Isolated Locations

- Mistrust of Government

- Access to Health Insurance Coverage

- Lack of Cultural Humility and Culturally Responsive Care

- Language Barriers

- Socioeconomic Status

All of which perpetuate poor mental health outcomes in Indigenous communities.

Mental Health in LGBTQI+ Communities

LGBTQI+ communities comprise lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex communities. Members of the LGBTQI community are also diverse in race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, socioeconomic status, and the like. The intersectionality of these identities creates a strong sense of pride and resiliency among members of this community.

According to recent research, members of LGBTQI communities are at serious risk of mental health conditions due to the levels of intersectionality and oppression they must navigate.

NAMI reports that LGB adults and youth are more than twice as likely to experience a mental health condition while transgender individuals are nearly four times as likely to experience mental health conditions as their cis, heterosexual counterparts.

Risk Factors of Poor Mental Health in LGBTQI+ Communities

Several risk factors must be identified and when navigating mental health in LGBTQI communities.

- Coming Out

- Rejection from society and social support groups

- Trauma, including homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and violence/hate crimes against LGBTQI communities

- Substance Use as a coping mechanism

- Homelessness

- Death by Suicide

- Inadequate Mental Health Care Services

All of these risk factors increase the allostatic load and contribute to the poor mental health of LGBTQI communities.

Mental Health Care in Individuals Living with Disabilities

According to NAMI, there are 61 million Americans living with disabilities. The term “disability” may refer to physical or mobility-related disabilities, cognitive, developmental, or intellectual disabilities, and/or sensory disabilities (blindness or deafness).

People living with disabilities are often faced with discrimination that hinders their access to employment, housing, medical care, and coverage.

Likewise, people living with disabilities may identify with other intersectional groups along race, ethnic, sexual orientation, and gender communities.

The combinations of discrimination based on ability, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity lead to disparities in mental health outcomes for individuals living with disabilities.

Navigating the isolation from being excluded from social activities or recreational events may also lead to poor mental health and higher risks of mental health conditions.

Barriers to Mental Health Care in Individuals Living with Disabilities

Many of the same barriers that exist across communities also exist for those living with disabilities. These barriers may include:

- Lack of Integrated Care

- Socioeconomic Status

- Employment Status

- Communication Barriers

- Financial Barriers

These barriers often lead to individuals living with disabilities refraining from seeking mental health care.

Mental Health Inequities among Individuals with Mental Illnesses

The CDC has reported that certain mental health conditions are related to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 infection. Those conditions are:

- Mental health disorders limited to: Mood disorders, including depression, and Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Ceban et al. noted in an October 2021 study that certain mood disorders that impair immune function, coupled with social determinants of health, increase the risk of COVID-19 in vulnerable populations.

Still, Fond et al. noted in a November 2021 study that other factors that lead to inequities in patients living with mental health conditions, such as barriers to access to care, the effects of psychotropic drugs, the social determinants of health, and immune disturbance may lead to disparate COVID-19 health outcomes in patients with mental conditions.

Because the nuance of these inequities exist in the intersectional spaces of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, clinicians must understand these nuances when seeking to provide mental care for patients with preexisting mental conditions.

With the insurmountable oppression that many marginalized and historically excluded communities face, the allostatic load of each population must be considered when attempting to create equitable mental health spaces for communities to safely exist.

The Pandemic’s Toll on Mental Health

COVID-19 Death Toll

As of May 16, 2022, the U.S. has seen nearly 1 million deaths from COVID-19.

Globally, the death toll from COVID-19 is about 6.26 million

Trauma, death, and grief on a scale as large as this is bound to have a lasting effect on a society.

In March 2021, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) reported that 1 in 4 U.S. adults reported having a close friend or family member who died from COVID-19 complications. Approximately three in ten of these individuals said that the stressors of the pandemic had a “major impact” on their mental health.

An additional 12% reported someone less directly connected to them had died of COVID-19.

Many people who were adjacent to death from COVID-19 weren’t even allowed to say a proper goodbye or give a proper burial ceremony for their loved ones.

It can be reasoned that this catastrophic level of death may contribute to the allostatic load and poor mental health of an entire global population.

KFF reported that nearly half of those who said they had someone close to them die of COVID-19 said their mental health was impacted in at least a minor way and those who had not had a personal experience with someone dying from COVID-19 said the same.

Working During the Pandemic

Working during a global pandemic is already stressful enough. Factor in the need to socially and physically isolate because the virus causing the pandemic is transmissible via aerosol droplets and you’ve made one perfect storm for poor mental health and mental health conditions to emerge.

Essential workers had to live and work through an extra added layer of mental health risk. The sheer nature of their jobs being essential placed them at risk for catching COVID-19, thus adding mental health stressors to their lives. Industries and positions that absorbed the brunt of these stressors had a unique mental health maze in which to navigate.

Service industry workers (food, grocery stores, delivery services, etc.) had to attend a regular work schedule to keep food on the tables of the population and to deliver essential items (toiletries, clean drinking water, etc.). Many workers in the service industry lost friends and colleagues to the virus.

Healthcare providers on the frontlines caring for patients who had contracted COVID-19 were among the most vulnerable. Nurses, doctors, medical assistants, speech pathologists, etc. were in direct contact with the virus. Personal protective equipment (PPE) was in short supply. Their hours were long and arduous. All of which contributed to healthcare provider burnout. Still, a study by Prasad et al. noted that stress related to the pandemic was highest amongst nurses assistants, medical assistants, social workers, inpatient workers, women, and persons of color.

Public health professionals around the country (field epidemiologists, contact tracers, leaders at state and local public health departments, etc.) received death threats and general disdain from their communities. They were also in a constant state of professional anxiety, attempting to create mitigation strategies, engage in infectious disease surveillance, and work with doctors and scientists to end the pandemic. These stressors caused many to leave their professions.

Faith-leaders, especially Black and rural clergy, expressed that the pandemic had a highly negative impact on their mental health. The experiences of closing faith meeting spaces coupled with holding many funerals for congregants and their family members took a great toll on their mental health. A research study by Williams et al. aimed at understanding the mental health of white Appalachian congregants and Black nonrural congregants even found that all respondents had a high perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 (54%) but 33.2% expressed they may not receive the COVID-19 vaccine if offered.

A Faith Leaders Perspective:

Pastor Bowens’ from Health Champion’s Faith Health Alliance shares his story from overseeing a congregation during COVID-19.

The Pandemic’s Toll Across Generations

According to KFF, younger adults (who may be more likely to report mental health trauma) were more likely to report that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted their health.

In addition, Black adults (49%), white adults (48%), and Hispanic adults (43%) said that the pandemic negatively impacted their health.

Adults ages 65 and older were among those in a smaller proportion to note that the pandemic had a negative impact on their mental health, though older adults and Black men may be less likely to report on their mental health.

The Pandemic’s Toll Across Genders

KFF noted that more than half of women (55%) reported a negative impact on their mental health as a result of the pandemic, while only 38% of men reported the same.

Mothers who stay at home with children under the age of 18 also reported varying degrees of the negative impacts of the pandemic on their mental health.

Approximately 69% of women ages 18 to 29 reported negative impacts on their mental health. It should be noted again that older populations are less likely to report on their mental health.

Access to Mental Health Services During the Pandemic

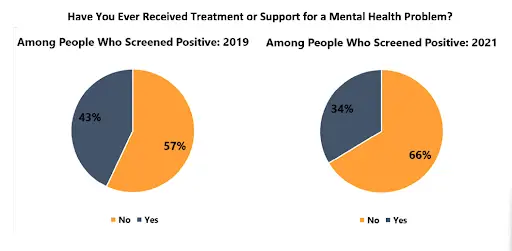

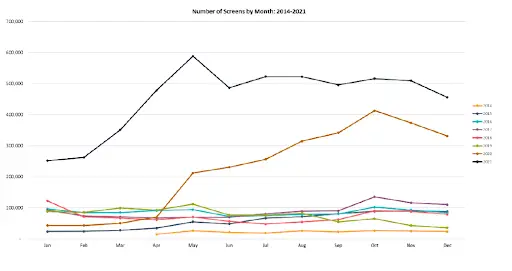

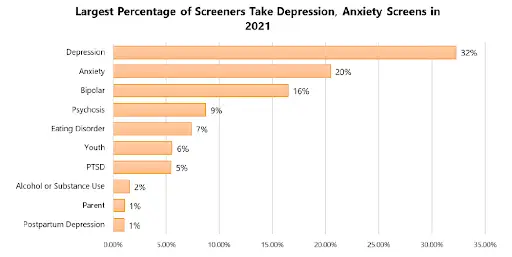

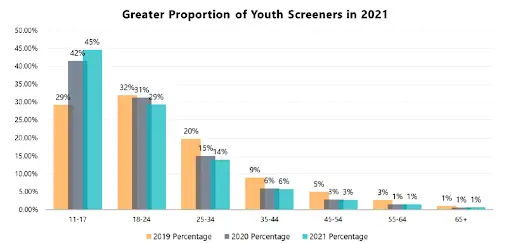

In April of 2022, Mental Health America reported that the rates of people looking for online mental health services increased significantly from 2019 – 2021. Specifically, in 2021 the number of people who took a mental health screen increased by 500% from that of 2019 and a 103% increase from that of 2020.

While most services moved to completely online/telehealth structures, many communities experiencing the digital divide (having less or no access to technology) were not able to participate in mental health care in this way.

This created new stressors that contributed to pandemic anger, pandemic burnout, anxiety among Black Americans, and suicidal ideations among several marginalized groups.

Mental Health of Black Americans during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Disparities in Outcomes

Many Black communities suffered most during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was due to a number of reasons.

- Higher proportions of essential workers especially vulnerable to the disease

- Multi-generational homes

- Limited or no access to high-quality healthcare

- Cultural tendency to gather and congregate

- Lack of access to vaccinations

- White communities being vaccinated in communities where vaccine rollout was specific and prioritized Black communities

- Discrimination and racism in healthcare

- Lack of access to high quality risk mitigation measures (KN95, N95 masks)

- Inability to socially distance due to work requirements and financial inequities

- Lack of vaccine communications with culturally responsive messages and images

- Mistrust of the medical, public health, and governmental systems

- Many more…

Existing while Black During a Pandemic

Attempting to navigate a pandemic in which all of the existing barriers, disparities, and inequities are magnified amongst your population can lead to many psychological risks.

Snowden & Snowden note that even without the pandemic, Black communities have a plethora of social, political, and systemic determinants of health to endure, navigate, and attempt to solution for.

Thus, dealing with COVID-19 illness, deaths, and transmission breaks down the resiliency and mutual connectedness of Black communities.

The effects of the pandemic on Black communities are unlikely to dissolve as we move into a future of endemic COVID-19.

Most will struggle with long hauler COVID, the grief of lost loved ones, the financially toxic impact of the pandemic, and the ever persistent disparities in care that already existed.

Solutions

Snowden & Snowden recommend outreach to Black communities through trusted community actors and leaders as an evidence-based strategy to improve the community’s mental health.

Novacek et al. challenges clinicians and researchers to consider the unique mental health position of Black Americans. One that includes the historical contexts on racial trauma and mistrust of most American systems.

Online psychotherapy is an option for most who have access to technology.

Resources for The Pandemic's Toll on Mental Health

Resources from Mental Health Collaborative

General Mental Health Information

Self-Screening Tests

For Youth

For Parents and Caregivers

For Public Health and Health Professionals

COVID-19 And Mental Health

For Employers and Employees

Watch Now:

The Pandemic's Toll on Mental Health

You’re invited to join NMQF’s Center for Sustainable Health Care Quality and Equity (SHC) for a Health Champions discussion on “Champions for Total Health: Black Maternal Health & Vaccines” with a focus on flu and COVID-19 vaccination rates and additional inequities in the African American community.

Panelists:

Richard E. Harris II, MD, PharmD, MBA Founder, Great Health Wellness Host, the Strive for Great Health Podcast

Reverend Dr. Thurmond Bowens, Jr. Pastor, Trinity Baptist Church

Trevor Jennings Senior REACH Program Coordinator Association of Immunization Managers (AIM)

Kristen Hobbs, MPH, CPH Director, Quality Improvement & Equity Center for Sustainable Health Care Quality and Equity National Minority Quality Forum ( Moderator)

Sources:

Asian American and Pacific Islander. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Asian-American-and-Pacific-Islander

Audrey Kearney Follow @audrey__kearney on Twitter, L. H. F. @lizhamel on T., & 2021, A. (2022, March 4). Mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: An update. KFF. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/mental-health-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/#:~:text=In%20the%20first%20few%20months,53%25)%20in%20July%202020.

Ceban, F., Nogo, D., Carvalho, I. P., Lee, Y., Nasri, F., Xiong, J., Lui, L. M., Subramaniapillai, M., Gill, H., Liu, R. N., Joseph, P., Teopiz, K. M., Cao, B., Mansur, R. B., Lin, K., Rosenblat, J. D., Ho, R. C., & McIntyre, R. S. (2021). Association between mood disorders and risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(10), 1079. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1818

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 28). About mental health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 15). Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html#anchor_1618433687270

The difference between mental health and mental illness. We Are Wellbeing. (2020, June 2). Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://wearewellbeing.co.uk/insights/the-difference-between-mental-health-and-mental-illness/

Duru, O. K., Harawa, N. T., Kermah, D., & Norris, K. C. (2012). Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality. Journal of the National Medical Association, 104(1-2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30120-6

Fond, G., Nemani, K., Etchecopar-Etchart, D., Loundou, A., Goff, D. C., Lee, S. W., Lancon, C., Auquier, P., Baumstarck, K., Llorca, P.-M., Yon, D. K., & Boyer, L. (2021). Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(11), 1208. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274

Hispanic/Latinx. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Hispanic-Latinx

Indigenous. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Indigenous

LGBTQI. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/LGBTQI

Mental health and covid-19: Two years after the pandemic, mental health concerns continue to increase. Mental Health America. (2022). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://mhanational.org/mental-health-and-covid-19-two-years-after-pandemic

Mental health conditions. NAMI – National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Black/African American. NAMI – Black/African American. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Black-African-American

Novacek, D. M., Hampton-Anderson, J. N., Ebor, M. T., Loeb, T. B., & Wyatt, G. E. (2020). Mental health ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Black Americans: Clinical and research recommendations. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 449–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000796

People with disabilities. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/People-with-Disabilities

Prasad, K., McLoughlin, C., Stillman, M., Poplau, S., Goelz, E., Taylor, S., Nankivil, N., Brown, R., Linzer, M., Cappelucci, K., Barbouche, M., & Sinsky, C. A. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A National Cross-sectional Survey Study. EClinicalMedicine, 35, 100879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879

ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Allostatic load. Allostatic Load – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/allostatic-load

Snowden, L. R., & Snowden, J. M. (2021). Coronavirus trauma and African Americans’ mental health: Seizing opportunities for transformational change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073568

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. MedlinePlus. Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://medlineplus.gov/obsessivecompulsivedisorder.html

Williams, L. B., Fernander, A. F., Azam, T., Gomez, M. L., Kang, J. H., Moody, C. L., Bowman, H., & Schoenberg, N. (2021). Covid‐19 and the impact on rural and black church congregants: Results of the C‐m‐C Project. Research in Nursing & Health, 44(5), 767–775. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.22167